For the February 2015 issue of Together magazine, I wrote about “Late Bloomers”.

I consider myself a bit of a late bloomer. My love of writing, reading and philosophy only came to me later in life. I certainly recall hating reading as a child and the only writing I enjoyed was doodling a few poems here and there on the back cover of my exercise books. As for philosophy, well that involved reading so enough said. I did, however, have an inquisitive mind.

I was (and am) particularly struck by very talented people who also happen to be very young. Unfortunately, it is more out of envy rather than awe or admiration. To appease my jealousy and reassure me that it’s ok to be one, I embarked upon a quest to discover late bloomers. I learnt about many a late bloomer, some to my surprise and perhaps to yours.

Although it’s wonderful to marvel at the great, late bloomers, we should just as well welcome the lesser known ones: those who flourished in adversity; or those that found joy in finally finding something they enjoy doing and became good at, e.g. cooking, aromatherapy, mentoring, DIY.

Here’s a short excerpt to entice you with the link to the magazine. It’s on page 29 of the magazine (p. 15 of the Pdf). Alternatively you can read a shortened online version. But to get a good sense of what I’m talking about, read the full magazine version.

Enjoy and do leave me a comment. Are you a late bloomer? I would love to hear from you.

Late bloomers : Gemma Rose writes in praise of those whose talent bloomed later in life

At last year’s TEDxBrussels, I was particularly struck by one of the speakers, Lina Colucci, who spoke about health hackathons. Health hackathons bring together specialists from different disciplines as well as consumer groups to respond innovatively to medical problems. At the age of 16, Lina began redesigning the ballet shoe so as to limit the pain and deformity done to the ballerina’s foot. This award-winning idea led her towards collaborating with Nike in updating the pointe shoe. Currently, she is a PhD student on a joint MIT and Harvard programme, dances ballet with the Harvard Ballet company and is an accomplished clarinetist. Judging by her CV and her appearance, she could not have been any older than 25.

Society tends to place a lot of value on youth. We often hear of the meteoric rise of actors, musicians, entrepreneurs, CEOs and inspirational leaders in their twenties, sometimes even in their teens. Forbes magazine does an annual “30 under 30” with movers and shakers in several domains including law and policy, education, entertainment and social entrepreneurship. This phenomenon is nothing new. Some of the greatest artists, composers, writers and scientists were so notable in part due to their youth – Picasso became well-known at 26, Mozart at 21, Orson Welles at 25 and Einstein at 26.

Read more… (pp. 15 – 16 on the Pdf)

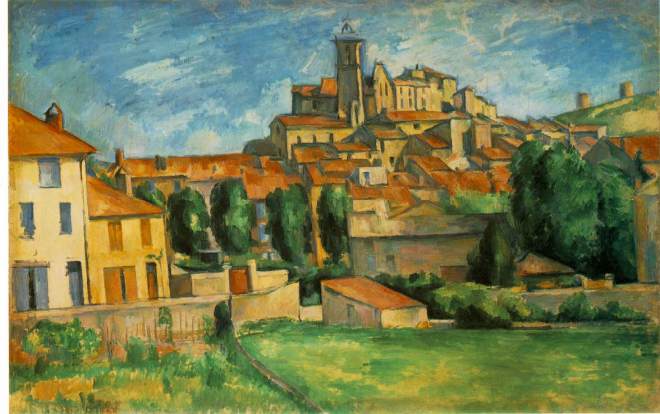

Gardanne (1885 – 86) by Paul Cézanne, a late bloomer.

References

Late Bloomers, Malcolm Gladwell for The New Yorker

Interview with Uncle Yee, Lite FM

The Meaning of Things, A.C. Grayling

Why we should all hack medicine, Lina Colucci, Tedx Brussels 2014

It’s not too late to make a difference, Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein, Tedx Brussels 2014